Improving Diabetes Care

Improving Diabetes Care

1 in 3 New York State residents with diabetes now have access to the best standard of diabetes care possible.

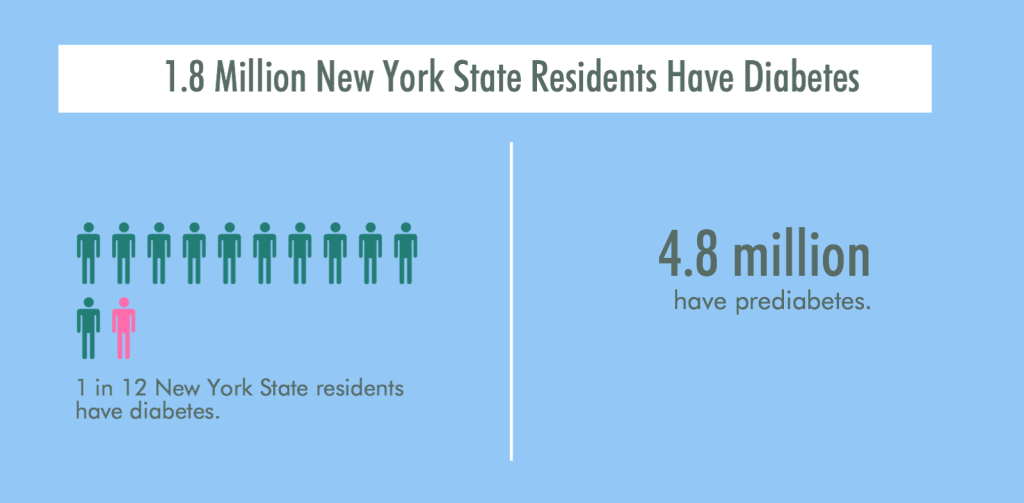

Nearly 1.8 million people in New York State – or roughly 1 in 12 residents – have been diagnosed with diabetes. Another 4.2 million have prediabetes.

Unlike other chronic conditions, such as asthma, for which rates are declining, the rate of diabetes among adults in New York has more than doubled since 1994 and is expected to double again by 2050. The diabetes epidemic, both nationally and in New York State, is a growing and serious challenge to our public health system. Not only is diabetes costly – 1 in 5 dollars now spent on health care goes toward treating diabetes – the human toll is enormous. Diabetes is a leading cause of blindness and disability and increases the risk of heart attack, stroke, and a host of other serious complications.

Reducing the prevalence of diabetes is key to improving the health of all New Yorkers, which is why improving primary care and outcomes for patients with Type 2 diabetes was an initial area of focus for the New York State Health Foundation (NYSHealth) when it launched in 2006. As the only statewide foundation in New York State, we had a charge much bigger than our $280 million bank account: we wanted to make a measurable difference in New Yorkers’ health and lives.

To have the meaningful impact we were aiming for, we chose as one of our goals improving the quality of care that diabetes patients in New York were receiving. A landmark national study found that only 45 percent of patients with diabetes were receiving recommended care for their condition, with only 24 percent getting regular blood sugar checks. In addition, a national survey found that only about 7 percent of patients with diabetes had well-controlled blood sugar, blood pressure, and cholesterol.

More than 3,000 physicians in New York State have now achieved recognition for providing excellence in diabetes care.

Our goal in this area was straightforward: we wanted to help 3,000 primary care providers in New York State achieve recognition from the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) for excellent diabetes care by the end of 2013. This program was especially attractive because it signified that providers were not only delivering the right care processes (like conducting regular foot and eye exams on patients with diabetes) but also achieving good outcomes, such as controlled blood sugar, blood pressure and cholesterol levels among patients with diabetes. Moreover, research shows that these clinical standards of care can reduce the risk of complications associated with diabetes, such as heart disease, stroke, kidney disease, and blindness.

Image credit: Roj Rodriguez, courtesy of New York State Health Foundation

We chose 3,000 as our target number because that’s the number of providers who care for approximately one-third of New Yorkers with diabetes. If we could ensure that 600,000 patients had excellent care and outcomes, we felt that we would reach sufficient scale to achieve meaningful change. Success among 3,000 physicians could also encourage others to follow their lead.

Our initial strategy was to work with four statewide professional associations of primary care providers to get the word out to their members about the NCQA program and help them through the recognition process: the Healthcare Association of New York State (HANYS), the Community Health Care Association of New York State, the New York State Academy of Family Physicians, and the New York chapter of the American College of Physicians.

While we made good initial progress with this strategy, momentum began to stall after an initial cohort of early-adopters achieved recognition. By September of 2010, only about 700 providers had been recognized (up from a baseline of 149 in 2007), and the pipeline seemed to be drying up.

Though we could have called it a day at this point – after all, 1,000 health care providers delivering excellent diabetes care is a significant achievement – we decided instead to tweak our strategy to reach a goal we believed in.

So what did we do? We decided to reach out to physicians directly, offering $2,500 grants per provider to help them achieve NCQA recognition.

Some of these awards went to large health care systems with multiple providers, but we also worked with small practices and even solo practitioners. For all of them, we used a pay-for-performance model, awarding 20 percent of the grant upfront and paying the remaining 80 percent only when providers achieved the recognition. This was an unusual practice for us—normally we award 80 percent of grant dollars at the outset—but we knew that a different approach was needed if we wanted a different outcome for this particular program.

We also continued to work with HANYS (whose members ultimately comprised about half of the NCQA-recognized physicians in New York State) to reach its late-adopter members, who required a bit more cajoling than the early adopters to pursue the diabetes recognition. With additional funding from NYSHealth, HANYS provided $600 incentives to 200 or so of its members to encourage them to apply for and achieve recognition. The tangible benefit of these incentives helped to earn the attention and support of hospital leaders who had not previously been engaged. We heard from hospital leaders that, as a result of pursuing and achieving recognition, diabetes went from a “hidden disease” to a top priority.

By the end of 2013, we squeaked over the finish line: 3,081 primary care providers in New York State were recognized by NCQA for delivering excellent care for their patients with diabetes. More than 600,000 of the 1.8 million New Yorkers with diabetes would now be getting the best possible care for their condition. And the providers who treat them have invested in changes to their internal processes and practices to ensure that these improvements are sustained.

Image credit: Roj Rodriguez, courtesy of New York State Health Foundation

For example, one family practitioner who achieved recognition, Dr. Allen L. Fein, says participating in our program helped him significantly improve his patients’ care. “[C]ontrary to what I had expected, it was clear that I was quite far from meeting NCQA goals,” he said. “Being a diabetic myself, I was familiar with and supported such target goals. I had thought that my patients were getting very good care, so this was quite an eye-opener for my staff and to me personally.” Among the changes Fein instituted were to set up “focused” diabetes care visits, including appointments for his patients to received dilated eye exams. He also created new processes to ensure that each patient’s treatment goals were being monitored and that no one would fall through the cracks. Since implementing these changes, Fein has led several workshops for his peers to share what he’s learned and best practices.

Stories like these make us extremely proud of our ability to work both hard and smart to achieve our goal. Steve Schroeder (my first CEO when I worked at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation) liked to say that “execution trumps strategy,” and I was proud that we were able to apply that principle successfully in this case at NYSHealth. Having a clear and public goal—to improve diabetes care from 3,000 providers—was part of what motivated us to be creative and to figure out how to achieve success, by any means possible.

By helping to set the standard for diabetes care in New York State, we feel confident that our work will lead to a better quality of life for all New Yorkers.

James R. Knickman is the Former President and CEO of the New York State Health Foundation.

Project

Excellence in Diabetes Care

Philanthropy

New York State Health Foundation